|

| Margaret Gillies' restored portrait of Charles Dickens (extracted) |

The museum acquired the item through the aid of a successful fundraising campaign backed by generous private donations in addition to substantial grants from the Art Fund and the lottery-funded Arts Council England/V&A Purchase Grant Fund. Together, donors raised £180,000 for its acquisition of the historic painting.

The portrait in question, a miniature for which Dickens actually sat, is the work of Margaret Gillies, an early supporter of women's suffrage and vocal social reformer of the destitute in Victorian society. Gillies' politically motivated illustrations, submitted anonymously, had appeared in her common-law husband's (sanitary reformer and physician Dr. Thomas Southwood Smith's) 1842 report for the Royal Commission of Inquiry into Children’s Employment in Mines and Manufactories as a form of silent protest.

It was this bold and unyielding yearning for social reform and alleviation of poverty which first attracted Dickens to Gillies, who shared the writer's philosophies. Together, the pair would collaborate on a new portrait of Charles in late 1843. It was a pivotal moment in Dickens' career: a period of riding high off of the success of his second novel - a serial published several years earlier which we know today as the famous Oliver Twist - was beginning to wane. Dickens' subsequent works were critical flops (perhaps the greatest being Barnaby Rudge: A Tale of the Riots of Eighty, published in the 1840-1841 weekly serial Master Humphrey's Clock) and as a result, funds were becoming spurious for the frazzled writer. Something had to be done, and fast, at that - to preserve his former image as a revolutionary literary mind - an icon in the making. Dickens was living in full-on damage control mode.

Extant correspondence from Dickens to Gillies preserved at the museum authenticates the sitting: a letter dated "twenty-first July, 1843" (an excerpt of which is seen above) confirms the struggling writer's appointment, which Dickens notes is to occur some two days later, on "next Tuesday, at 12."

|

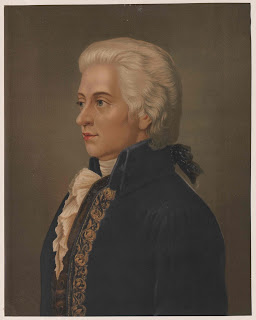

| Charles Dickens by Daniel Maclise, 1839 Click to enlarge image. |

This seemingly minor request posed to Ms. Gillies, when sufficiently analyzed, speaks volumes about Dickens' penchant for a controlled social presence, shouldered by a keen sense of self-marketing. The distinguished, worldly visage previously offered by Maclise (pictured left) was the very image the artist wanted to portray to the world - in particular to his finicky readership - who might have otherwise taken his latest literary failures as an indicator of a here today, gone tomorrow talent: a former rising star who wasn't quite up to cuff, who simply didn't have that certain Je ne sais quoi to make of himself a serious writer.

It was therefore crucial for Dickens that Gilles' portrait be not only true to life, but regal, powerful, polished. And that it was. Gillies' Dickens presents the writer in distinguished, muted tones - his otherwise child-like face is transformed into a state of burgeoning manhood. His doe-eyes penetrate the viewer head on, the nasolabial folds at either side of his mouth appear uncensored, on prominent display. This ingenious blend of youth and maturity exude a ripening sense of the boy-turned-man. Unlike Maclise's portrait, wherein Dickens fails to engage the viewer, Gillies portrait has him grip the viewer by the collar, and demands of him a listen. The portrait portrays a force - a man - to be reckoned with.

|

| Fans of Classical Music iconography may be familiar with Maclise's sketches of Niccolò Paganini. This drawing, in pencil, is titled "Debut in London of Nicolo [sic] Paganini"[1] (1831) (Click to enlarge image) |

For some 130-175-plus years, little was known about the location of Gillies' portrait. The mystery began as late as 1886, and the question of its whereabouts confounded even the artist herself, as evidenced in a surviving correspondence dated that year between Gillies and contemporary Dickens researcher Frederick Kitton, who wrote to the artist to inquire about the miniature for an upcoming illustrated project. Gillies response was less than revelatory: "I have lost sight of the portrait itself."

According to the British specialist art dealer Philip Mould & Co., there has been made no record of the whereabouts of the Gillies portrait since its display at the Royal Academy in 1844 - that is, until now.

Enter into timeline one Emma Rutherford, Portrait Miniatures Consultant for Philip Mould & Co. who recently received an email identification request from a gentleman in South Africa who had acquired a "box of household trinkets" from a local auction house. His purchase seemed on face value to have been run of the mill, nothing extraordinary - the auction house from which he made the purchase failing to single out any particular "trinket" as an item of interest. What he had, after all, was covered in a thick, virulent yellow mold - a result of the 19th century practice of mixing in paint gum with the watercolor - its subject indistinguishable. For Rutherford and the staff at Philip Mould, however - who frequently sift through identification requests, the reaction was quite a bit more surreal. They recognized the portrait as Gillies original - an authentication which would later be positively confirmed. Both the artist's technique and distinctive mount matched known examples by Gillies, and further research into her family tree revealed a crucial link between the artist and South Africa, where the portrait was ultimately found.

The painting's journey toward the "Rainbow Nation" began with the extended family of Gillies' adoptive daughter, whose brothers-in-law would become early settlers at the British colony of Natal (present day Kwa-Zulu Natal) - the very spot miniature was found.

The portrait, which has been restored to its original lustre through the skilled hands of a conservator at the Victoria & Albert Museum will make its modern day "premiere" this fall as the Charles Dickens Museum prepares to present it to the public beginning October 24. While the portrait's true modern debut occurred this past April, on the 2nd - 7th in Dickens' study at 48 Doughty Street, the display was brief - the mid-campaign event launched to bring awareness to potential donors who could aid in the museum's acquisition of the portrait. The launch this October will present the miniature for the first time in its permanent home.

It will be an especially exciting display for fans not only of art but of the author Dickens: dealer Philip Mould, speaking in a brief presser shot by the museum made quite an astute observation when he recalled a reference made by Dickens himself - his very first - concerning "A Christmas Carol" during a time frame which coincides exactly with the days he would have been sitting for his portrait with Gillies. Considering the pair shared a similar social ideology, Mould aptly posited, it could be argued that Gillies herself could have possibly influenced what would become Dickens' career-saving, everlasting hit. If this is accurate, it makes this portrait in particular far more invaluable to the Dickens legacy.

Did You Know?

| An excerpt from a production of the little known singspiel written by Goethe for Corona Schröter's "Die Fischerin." Intended for open air performance at Weimar in 1782, it premiered that year in the park at Tiefurt on the banks of the Ilm river. Goethe was by all accounts a man of many hats - he served as co-designer of both Tiefurt and Beledere Parks, both situated along the Ilm. They, alongside "Goethe's Gardens" are today designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site. |

Dickens himself incorporated music into his works, however they were not orchestral, nor operatic in nature - save for a nod to George Frederic Handel in the dialogue of Pip, the main character in Charles' 1861 "Great Expectations" who is assigned the nickname "Handel" by the character Herbert Pocket (as a reference to the former's upbringing.) "We are so harmonious -- and you have been a blacksmith --- would you mind it?...There's a charming piece of music by Handel, called the Harmonious Blacksmith" Dickens writes.

Rather, it is simple dance tunes that would have been heard in the domiciles of the everyday Englishman's family home or whilst outdoors, enjoying a leisurely stroll that are given preference. A frequently heard domestic staple in the era of Charles would have been "The College Hornpipe," a jaunty instrumental dance number which made its way into the pages of 1848 "Dombey and Son" and his 8th novel, published in 1850 "David Copperfield."

Songs and ballads were also included in Dickens' works, such as "The Ivy Green," which appears in "The Pickwick Papers." Their inclusion in his novels is perhaps a nod to his beloved past time of singing. This adoration for the common musical fare of domestic and street musicians, however, had its time and place - Dickens was known to abhor such distractions whilst engaged in writing.

| Above: Dame Janet Baker sings the aria "Che farò senza Euridice" in her final performance as Orfeo (and in her farewell to the operatic stage) in Peter Hall's 1982 Glyndebourne production of Gluck's Orfeo ed Euridice. It is easy to see why Dickens admired this work - Charles famously attended a performance of this beloved opera while in Paris, with confidante Arthur Sullivan in tow. |

The beautifully composed music is classic Bax: lush, thrilling, and incredibly picturesque. The masterful score, arranged by Muir Mathieson as an orchestral suite under the composer's supervision, can be heard below (split into two videos - part two here):

In addition, the late, great German lyric baritone Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau paid his own tribute to Dickens in the form of recitation when he read a passage, in his native tongue, from "A Christmas Carol" - "Das war der Pudding," or, "That was the pudding," the track titled after a line in the novella's famed "pudding scene" - released in 2004 on the album put out by Claves Records, "Weihachten."

Listen below to Dietrich's reading, interspersed with "Mozart's" (attr./ K. Deest) fragmentary Piece in G major for Piano, performed by Duo Crommelynck. For reference (for my English readers) and to follow along, skip below to pages 84-89 of the interactive novella, A Christmas Carol, available in the public domain (and posted at the bottom of this article.) Reading begins on pg. 84 with "...Master Peter and the two ubiquitous young Cratchits..." and ends on pg. 89 with " 'A Merry Christmas to all, my dears, God bless us!' Which all the family re-echoed.")

Footnote:

[1]This lithograph after a drawing by Maclise depicts Paganini's London debut at the King's Theatre (Opera House) on 3 June, 1831 and was sketched live by the artist. Paganini is pictured three times in the drawing: at center, performing in front of 36 members of the in-house orchestra, and on the lower right and left corners under the central oval, where he can be seen bowing (L) and playing the violin (R.) The inscription at the bottom reads: "The Debut of Paganini / Harmonies & Seul Corde / Sketched at Opera House."

Paganini, by all accounts, dazzled London concertgoers, as well as the musicians in the Orchestra. His debut was the talk of the town long after the June 3rd concert, as evidenced by a raving review published the following month in The Harmonicon by editor, eminent musician and critic William Ayrton, who wrote:

"The long, laboured, reiterated articles relative to Paganini, in all the foreign journals for years past, have spoken of his powers as so astonishing, that we were quite prepared to find them fall far short of report; but his performances at his first concert, on the 3rd of last month, convinced us that it is possible to exceed the most sanguine expectation, and to surpass what the most eulogistic writers have asserted. We speak, however, let it be understood, in reference to his powers of execution solely. These are little less than marvellous, and such as we could only have believed on the evidence of our own senses; they imply a strong natural propensity to music, with an industry, a perseverance, a devotedness, and also a skill in inventing means, without any parallel in the history of his instrument."Another critic writing for the periodical The Athenæum shared an even more visceral sentiment:

"At length all differences have been arranged, and the mighty wonder has come forth—a very Zamiel in appearance, and certainly a very devil in performance! He is, beyond rivalry, the bow ideal of fiddling faculty! He possesses a demon-like influence over his instrument, and makes it utter sounds almost superhuman.... The arrival of this magician is quite enough to make the greater part of the fiddling tribe commit suicide."The concert brought in a total of £700 (£500 less than his subsequent concert at the theatre seven days later), with Paganini affirming his worth as a talent worth top dollar (he had previously failed to secure double the going rate prior to his debut.)

On the June 3 programme was Beethoven's 2nd, the concerto in E flat (Paganini's violin concerto in D was originally performed in E flat) and the musician/composer's own Military Sonata for the G string (Military Sonata on Mozart's "Non più andrai.")

-Rose.